5-star books: In Memoriam and Wandering Souls review

If you only read two books this year, let it be these.

In March this year, two of the most incredible debut novels I have read were published, In Memoriam by Alice Winn, and Wandering Souls by Cecile Pin. Last month, both books were shortlisted for the Waterstones Debut Fiction Prize 2023, an award created for exceptional debut novels voted for solely by booksellers. I am incredibly pleased they made the shortlist, having won my votes along with Esther Yin’s Y/N, Nicola Dinan’s Bellies and Lydia Sandgren’s Collected Works (unfortunately none of the latter three made the official shortlist, but if you trust me, then you should read them too). The official shortlist includes, Kala; Close to Home; Chain-gang All Stars and Fire Rush, pictured left. The winner will be announced on the 24th of August, and as you may guess, I am rooting for Alice or Cecile to take home the crown.

Both books are set in the past, exploring war and how its trauma affects us and our relationships in years to come. Whilst Winn’s novel tracks Gaunt and Ellwood, two English private school boys conscripted to fight in the First World War, Pin’s novel is set in Thatcher’s Britain, following three siblings fleeing their village amidst the Vietnam war. Both novels are meticulously researched, urgent and haunting with characters you will carry in your heart for a lifetime.

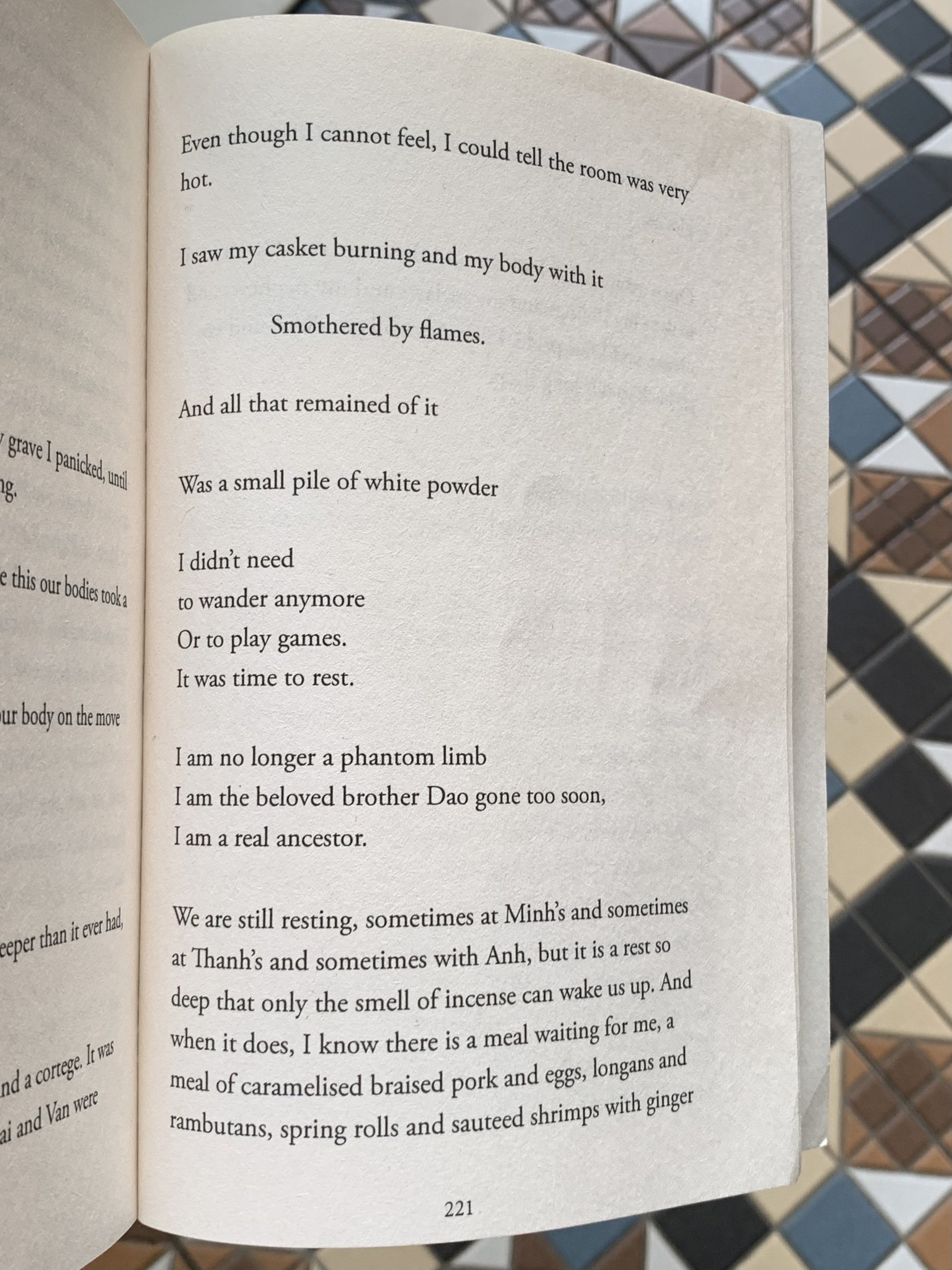

Wandering Souls is told from different perspectives using a range of important voices that span through time and across generations. One of my favourite narrative voices is that of Dao, the baby brother of siblings, Anh, Minh and Thanh, who along with their parents and other siblings, died on the crossing from Vung Tham. Pin writes from his perspective in harrowing poetic prose, often creating very visceral imagery, and yet he speaks with an innocence and longing that made my heart crack. Baby Dao serves as the voice of all the ‘wandering souls’, those who were denied the chance of growing up, learning to speak and read, of escaping their war-torn country, of falling in love for the first time, never able to join their families, to rest in peace. Indeed Pin’s need to write an ode to these wandering souls is both political and personal, she reveals in an exclusive with Waterstones that the novel is also her family’s story:

“my mother is a Vietnamese boat person who spent a year in a refugee camp in Thailand before settling in France with her brothers and sister. On the journey to Thailand, she had lost her parents and five of her siblings who had been travelling on different boats. This was not a heritage that was handed to me at birth, but one I had to learn bit by bit over the years. Snatches of events on the boat or at the camp were fed to me by my mum or my uncles, my father and sisters. Sitting down to write Wandering Souls, I realised that I wanted the book to reflect this scattered inheritance.”

The novel is metafictional, which happens to be my favourite literary style. The narrator directly addresses the reader at various intersections with diary-like entires, exploring the importance of (and sometimes difficulty that comes with) telling the stories of survivors and of those who are no longer with us:

“I want to make history vivid in my mind. And as my knowledge and understanding grows, I feel a responsibility to pass it on, as if I’d inherited this story, as if it is now my burden and my care. I cannot let it fade away; I cannot let it die”.

Central to the narrator’s research is the Koh Kra massacre of 1979. On a small island off the coast of Southern Thailand, boats of Vietnamese refugees fleeing the war were seized by gangs of fishermen from their refugee camps. Across 22 days, they were killed, robbed and raped. A CARE report regarding rape found a girl as young as nine to have suffered, as well as multiple girls aged only twelve to thirteen, victims of gang rapes. Dr Mehlert who conducted the report revealed that girls and young women aged 15-20 were likely to be raped over 50 times.

The narrator of Pin’s novel tells us that:

“After I learned about Kho Kra I couldn’t sleep for three days, and again I asked myself, why do I want to do this?

I guess it is more of a need than a want.”

I particularly admired this element of the book despite reviewer’s suggesting that the regular incisions of (arguably Pin’s) narrative voice disrupted the overall flow of the story. By zooming out and providing her reader with a raw opinion on the complexities of crafting a story about a large-scale tragedy whilst giving voice to the very real individual people affected by it, Pin deftly explores how generational trauma manifests in the day-to-day lives of those who must live on. After all, in her own words, “what better way is there of processing our past, than by rewriting it?”.

“Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all”

To describe Alice Winn’s debut in a nutshell, I would say imagine if Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name had a baby with McEwan’s Atonement. Like those texts, I know In Memoriam is one I will find myself coming back to again and again. Borrowing its title from Tennyson’s poem of the same name, this is a story of love, grief and longing. The story is told in third person, shifting perspectives between Gaunt; struggling with his feelings for his charming best friend, Ellwood, and Ellwood, who unbeknownst to Gaunt and at times himself, equally longs Gaunt’s affection. Set just before, during and after the First World War, this is the most realistic, visceral and profound modern depiction of being on the front line I have ever read. You truly feel like you are in the action - think Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan or Nolan’s Dunkirk. Perhaps it’s unsurprising then, that just before embarking on her research for In Memoriam, Winn, self-confessedly, was procrastinating on a screenplay.

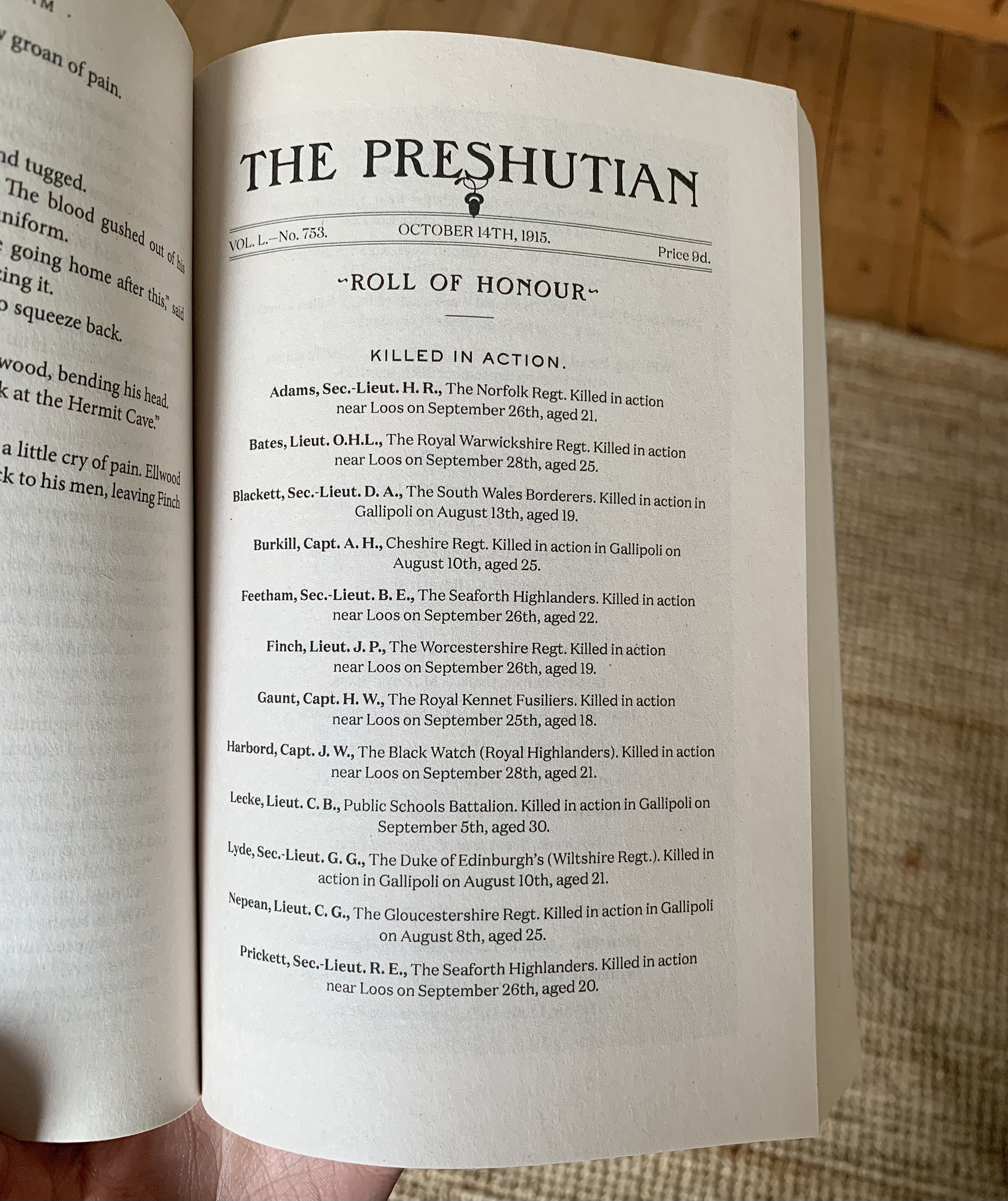

Winn studied at Marlborough College, to which the fictional school attended by Gaunt and Ellwood, Prehute, bears a striking resemblance. Soldier and leading war poet, Seigfried Sassoon, also attended Marlborough College (c. 1900-1905) and was integral to Winn’s development of this novel. In fact, it was her search for his poetry on the school website that lead her to uncover the school’s newspapers uploaded from the first thirty years of the 20th century. She read every paper from 1913 to 1919. Newspaper clippings, and especially ‘In Memoriam’s’ play a vital and shocking role in Winn’s storytelling. Turning a page can throttle you into the position of a young, petrified soldier as you scan the “Roll of Honour'“ of those wounded, missing or deceased, desperately searching but hoping not to find Gaunt’s name, or Ellwood’s or their friend Gideon Devi, or Roseveare or Burgoyne. As a plot device, this technique was phenomenal, almost too real. Winn’s novel reminded me of the power of fiction and why we so desperately need it - especially to give life to the those who are no longer here to tell their own stories.

Links to purchase can be found below: